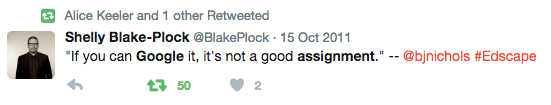

A few years ago, I ran across a tweet quoting Brian J. Nichols:

If you can Google it, it isn’t a good assignment.

This short tweet shifted my world. I look at the work my kids bring home through a whole different lens. Not that I ever approved of assessments that were based on simple factual recall – when I was teaching 20 years ago, we never ever used bubble tests. Those were considered the lazy teacher option that didn’t test anything except who had the best memory. In 1990, I was telling my history students that I didn’t expect them to memorize all the dates and facts as long as they knew how to find it. Back then, finding the information meant looking it up in a physical encyclopedia.

My daughter just finished her sophomore year of high school, including a year of AP World History. In this class and in her biology class she took a horrifying number of “Scantron” tests. Of course, the kids never got the tests back (you see, they might pass the answers to someone else) and parents never got to see them. I finally requested to see the tests and had to make an appointment so I could look at them in the room with the teacher present.

Back to Google….. After seeing the tests, I was so disappointed. They were 90% basic low level questions that could be easily answered using Google.

What about AP Tests?

A few months ago, I was asked to give a talk to a group of history and education majors at Carleton College about tech in education and how museums are using tech to work with the K12 audience. On a whim, thinking of my daughter’s tests, I looked for a sample AP test.

I took this sample AP test and Googled the 40 questions exactly as written. It took about 2 seconds to find the answers – and that was checking a couple of pages to verify the answers. Thirty-five of the 40 questions were easily answered this way. The other five required information from a chart or photo.

I asked the students at Carleton to find the answers to a couple of these questions. Obviously, they had the same result. The students, many of whom had taken plenty of AP classes, were shocked. The professors were very amused.

A few weeks after this, I had the opportunity to talk with a history professor at Oberlin College, and asked him what he thought about this and AP in general. He said that they often need to reteach students how to read and study history when they arrive at Oberlin. Students who have been through AP classes are geared to read for minutae and minor detail. They haven’t been taught to read for concepts, context and the big picture.

AP Philosophy

In looking closely at the AP material online, it turns out that the multiple choice questions and the free response questions are each worth half of a student’s “grade” on the test. There are 80 questions to be completed in 55 minutes. The free response questions, including primary source analysis and essay, takes 130 minutes.

This quote from the AP materials confuses me:

“Although there is little to be gained by rote memorization of names and dates in an encyclopedic manner, a student must be able to draw upon a reservoir of systematic factual knowledge in order to exercise analytic skills intelligently. Striking a balance between teaching factual knowledge and critical analysis is a demanding but crucial task in the design of a successful AP course in history .”

They admit that rote memorization isn’t necessary, yet fully one half of the test score is based on this skill. While I don’t disagree that a basic level of knowledge of factual knowledge is necessary, is it necessary to have grades depend on the skill of memorization when we now have access to encyclopedias of content in our pockets? There is no possible way we can have the entirety of knowledge memorized — we need to be able to find it. We need to teach students how to find this information.

In my daughter’s AP World History course, her assessment/grade was based on this skill of rote memorization: assessments were worth 60% of the grade, and these assessments were by far mostly multiple choice Scantron tests with a few writing assessments thrown in there. Any creative assignment that required critical thinking, creativity and communication was worth just a few points. The content, structure and assessment of the course is designed to heavily favor strong word-based learners. It does not allow for success of a visual learner.

Even Will Richardson dislikes Google Questions

At ISTE in June, Will Richardson shared a story about his high school daughter’s history final – 100 multiple choice questions. He thought that all but 5 could be answered using the phone.

“I’m a big advocate of open phone tests. If we’re asking questions we can answer on our phone, why are we asking the questions?”

I’m excited to have yet another awesome quote about the value (or lack of) low-level questioning.

I had a fun, quick Twitter interaction with him later — I just had to know what someone like him, who is so active in this community, so well respected, does when his own kid is given an assessment like this.

Watch Will’s talk. The history final story is at 12:30. Then don’t give any more tests that can be Googled.